The Most Profound Lesson In Product Didn't Come from A Product Person

What if the problem you're trying to solve doesn't really matter?

Before I began in product, I worked in sales to cover my bills. I had a sales coach at the time who taught me the most profound lesson I’ve ever learned about why people buy.

It’s a universal maxim that we can adapt to product management to answer the question:

How do we know if we’re building a solution to a problem that matters to our intended audience?

Sure, you can build the shiniest, coolest widget to solve a problem (or exploit an opportunity), but if it’s not a problem that matters to your audience, they won’t buy it or adopt it.

That’s why I emphasize the word, matters. There are problems we live with because they’re not worth the effort of addressing, and there are problems we’ll hand over blank checks for if we think they’ll bring us relief.

Think of it this way.

How much would you be willing to pay to remove a small scar on the back of your knee that you got from an injury as a child? Probably not much. Would you pay thousands out of pocket for something that’s unnoticeable that you’ve been living with for years?

Now, compare that to a situation where you walk into your doctor’s office for a routine physical and they say, “I’ve just taken a look at your bloodwork. Cancel whatever you have planned. I made you an appointment for an oncologist this afternoon.”

How much would you be willing to fix that problem? “Here’s a blank check, three credit cards, and everything else I own. Please fix me!”

The problem equation

Four variables determine if a problem matters enough to a customer or client to pay, invest time and resources, and take on the effort of fixing a problem.

Pain - It’s the driving motivator for buying decisions. Once we feel it, we will go to great lengths to eliminate it. It’s far more of a behavior influence than pleasure. Pain could be physical or emotional: a lack of status among your peers, a precarious financial position, a health issue, or the experience of embarrassment or humiliation. It’s also essential to note that a good marketing or sales team can reveal to potential customers pain they never knew they had.

Timeframe - When and for how long we experience pain also influences how much a problem matters. Pain in the present that we’ve experienced for a short period is more powerful than pain you might feel in the future. Pain in the present that has existed for a long time can work for or against you depending on the context. In some cases, it can build up over time to a point where the negative consequences of ignoring it add to the urgency. In other cases, people or businesses can adapt and accept it - they might have even adapted so well to it, that they will resist opportunities to fix it.

Threat - The threat of a negative outcome adds to the urgency. Perhaps I’m feeling pain, but I know that in a few weeks, it’ll dissipate or I’ll adapt. Getting passed over for a promotion might hurt in the short run. That person might feel tempted to hire a career coach. But after a few weeks, they adapt and accept their lot. Compare that to a business owner who just suffered a setback, and now is at risk of near-term bankruptcy. That’s pain. That person will be more motivated to take action because of the outcome expectation.

The cost equation

Cost represents the other side of the equation.

We tend to think money determines our audience’s buying decisions, but that’s only partially true. There’s time, effort, status, and risk involved too. All these factors battle out to see who wins: product adoption (buy) or inertia (do nothing).

The desire to conserve energy is baked into our DNA. If it’s easier to do nothing, that’s exactly what your target audience will do. We factor in inertia, the default behavior as the antagonist to product adoption.

Now that we know all the components, we can derive a formula:

If Pain + Timeframe + Threat > COC (cost of change: money, time, effort, status, risk) = Product Adoption wins over inertia

Conversely

If Pain + Timeframe + Threat < COC = Inertia or inaction wins over product adoption

The ‘cost of change’ components and their weight may vary depending on your audience. A consumer may not assess risk. They may consider money and status as prime factors.

Do all my peers have this product or are they using something else? Would this make me the outcast?

For some businesses, risk might be a minor factor whereas for others, like a bank, it may be the key component, so you would need to weigh each component appropriately. A business will consider status in reference to generally accepted solutions by peer businesses. For example, there’s the old saying, “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” This means that if you buy something from someone considered an industry standard, nobody will blame you if that decision backfires, but if you buy from an unheard-of organization, and it fails, you’re on the hook.

Status can work for or against you in determining cost. You will need to know your market well to assess these variables and weights.

The Action Inertia Matrix

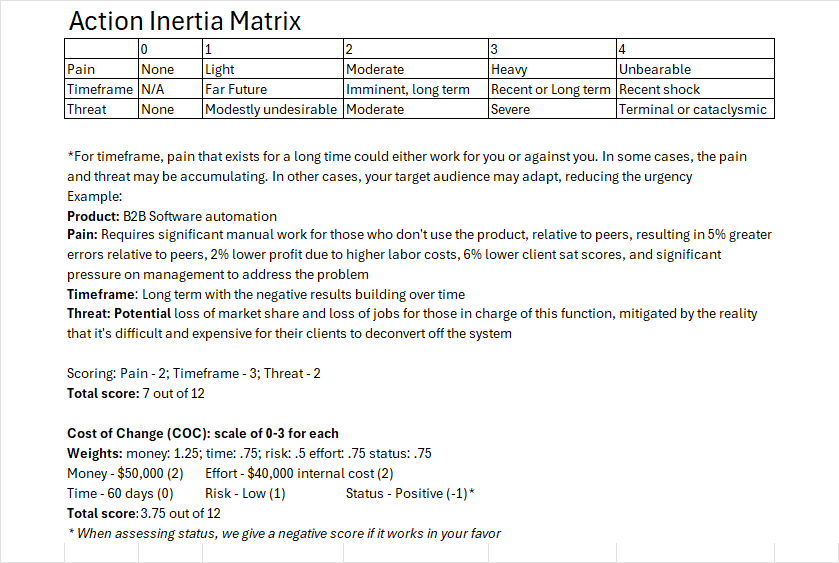

Once we gather all the components: pain, timeframe, threat, and COC (specific to your audience), we score all the variables.

Let’s assume this is a B2B product and the target audience is less concerned about risk and time than they are about the cost of the software and the internal resources required for onboarding and support. Let’s also assume, you’re recognized as an industry standard with a solid reputation, so buying from you represents a positive attribute when considering status.

This formula gives us a net score of 3.25. A positive number does not mean it’s a winner. It’s merely another way to assess if the problem you aim to solve matters to your intended audience.

Determining these scores requires a deep knowledge of your customer base, and in B2B, an understanding of not only your users but also those who make the buying decisions (often, it’s not the users themselves).